If you’ve been in business long enough, you’ve dealt with customers who are down on their luck. They may need to make installment payments over a few years to be able to afford their next purchase.

You don’t know if they’ll even be able to make the payments, but maybe against your better judgement, you approve the transaction.

It could be because you’re friends with the customer, because you have a long history of doing business together, or because you think maybe they actually can pull themselves out of the hole.

No matter why transaction is approved, you know there’s a distinct possibility you won’t be paid.

The cost recovery method was created for this situation. It allows companies to better recognize profit and defer taxes in uncertain situations.

Overview: What is cost recovery?

Cost recovery is a way of recognizing revenue. It’s used in instances where repayment is not guaranteed.

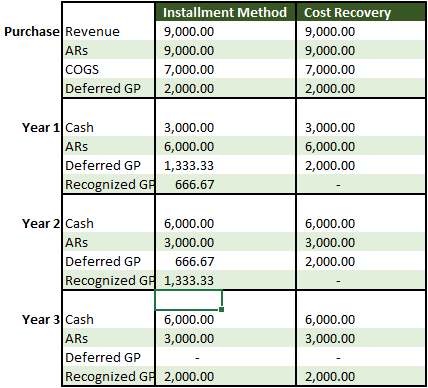

Normally, when a company is paid in installments, it uses the installment method to recognize revenue. Revenue and cost of goods sold are recognized at the time of sale, but gross profit is deferred to be recognized when cash is received.

When each installment of whatever percent of the total sale has been received, that percent of deferred gross profit is recognized. This ensures net income stays close to operating cash flow.

Where repayment of each installment is less certain, the cost recovery method holds off on recognizing gross profit until the company has earned back its cost of goods sold. That way, the gross profit doesn’t hit net profit (or affect taxes owed) until the business has recovered the cash outlayed for its costs.

How to calculate cost recovery for your small business

Let’s work through an example of how a transaction paid in installments would be recognized with both the installment method and recovery accounting.

Sam’s Sick Cycles sells a motorcycle to the owner’s wayward nephew, Gilbert Stanley, for $9,000 to be paid in three increments of $3,000 over three years. Sam’s cost of goods sold is $7,000 so the eventual gross profit on the sale is $2,000.

Gilbert can be a good kid, but he has a habit of over-promising and rarely keeps a job for more than a month or so. Sam’s makes the sale, hoping Gilbert can pull his life together, but knowing Gilbert will likely flake out on paying.

In both methods, $9,000 of revenue is booked during the purchase using gross method accounting — no sales discounts. Accounts receivable of $9,000 shows that no payments have been made, and the $7,000 cost of goods sold is entered to reduce the inventory account.

Deferred gross profit is created with a closing journal entry at the end of the first period, when the revenue and cost of goods sold accounts are closed:

| 12/31/2020 | Revenue | $9,000 |

| 12/31/2020 | Cost of Goods Sold | $7,000 |

| 12/31/2020 | Deferred Gross Profit | $2,000 |

With the installment method, the gross profit is realized in increments of $666 in each of the three years.

Under the cost recovery method, the cost of goods sold, $7,000, is not recovered in cash until the final year. So gross profit is not recognized until then, effectively acting as unearned revenue in the first two years.

Because the owner of the business is unsure whether Gilbert will make the incremental payments on time — or at all — the cost recovery method is a more conservative way of bookkeeping for the transaction.

If Sam’s had booked a portion of the gross profit in year one, and Gilbert had stopped paying, that profit would overstate net income. Sam’s would then have to write off the accounts receivable, showing a loss after it became clear that payments would never be made.

Depending on the operating expenses, the overstated gross profit increases the tax burden on the company. Sam’s is liable to pay taxes on the profit the year it is realized.

If Gilbert never finishes paying for the bike, there would be no refund for the tax paid — just a deduction in net income years later that would reduce the tax owed that year.

Is cost recovery the same as depreciation?

Depreciation and its cousins, depletion and amortization, are different forms of cost recovery deductions from the income statement.

When a business purchases an asset above a certain price (determined by the business), generally accepted accounting principles hold that the full purchase cannot be deducted on the income statement in the first year.

The business can recover the cost over the useful life of the asset. For fixed assets such as buildings and vehicles, that cost recovery is depreciation expense.

Depreciation can be calculated in a straight line — that is, the same amount is expensed each year — or you can use the IRS Modified Asset Cost Recovery System (MACRS). MACRS tells you what percent of the asset to expense each year.

Typically, business owners prefer MACRS because it allows them to recover the cost faster than the straight line method, which reduces taxes in the short term.

Amortization is used to recover the cost of large intangible asset purchases, such as software, and depletion is used to show the reduction over time in a natural resource asset, such as a mine.

The full cash amount is deducted from the cash flow statement as a capital expenditure in the year of the purchase. Underwriters use the free cash flow metric (operating cash flow – capital expenditures) instead of net income when analyzing businesses that make substantial fixed asset investments every year.

When not to use cost recovery

Business is about making tough choices, and at times, that means selling a product even if you’re not confident you’ll be paid. However, that doesn’t mean deciding how to account for those sales needs to be a tough choice. If you’re using good accounting software, it’s easy to choose the cost recovery method to do it right.

However, you shouldn’t use the cost recovery method for run-of-the-mill installment sales where you expect to be paid on time. It may sound appealing to defer taxes on the profit, but you’d be violating the accounting realization principle if you did so.

The realization principle states that revenue should generally be recognized when the product is transferred to a customer. Cost recovery can be an exception when you have a legitimate reason to doubt repayment, but if it’s used often, auditors won’t be happy.

The post A Small Business Guide to Cost Recovery appeared first on the blueprint and is written by Mike Price

Original source: the blueprint