That whole don’t-try-to-time-the-market thing may be resonating with some investors.

If you’re among those who headed for cash when stocks were down and now regret it, there are some things you should consider before jumping back in, experts say.

First, you better know thyself.

“If someone jetted out when the market was down and then gets back in, they probably would have the same reaction when it’s down again,” said certified financial planner Jeffrey Levine, director of advanced planning at Buckingham Wealth Partners on New York’s Long Island.

The S&P 500 index, while down roughly 4% for the year, is up more than 38% from its mid-March level of 2,237. The Dow Jones industrial average is down about 7.5% for the year but up 41.5% after dropping to 18,591 in March.

While it’s impossible to say with certainty where stocks will go from here, advisors say it’s important to make your investments intentional. That is, you should first make sure your entire portfolio reflects your short- and long-term goals for the money, as well as your risk tolerance (generally a combination of how long until you need the money and your ability to stomach volatility).

In other words, if you sold out of fear, your portfolio was likely too risky for you.

“No one complains when the market jumps 1,000 in a day, but that’s volatility,” Levine said. “If you can’t take the big lumps on the downside from time to time, you can’t be in that portfolio to enjoy the upside.”

Landing at the appropriate balance in your portfolio, Levine said, is where you should aim to be. “No one can predict when bear or bull markets end,” he said.

You also should ensure you have the cash cushion you need. For retirees, advisors often recommend keeping two to three years’ worth of income in investments that are not subject to the whims of the stock market.

“Say you spend $5,000 a month, or $60,000 a year — you’d put two years worth of that in cash or short-term treasuries or something else ridiculously safe,” Levine said.

And for those nearing retirement, your portfolio typically should be more conservative than when you were younger and farther away from needing to rely on your investments for income, said Kathryn Hauer, a CFP with Wilson David Investment Advisors in Aiken, South Carolina. She added, though, that everyone’s situation is different.

There are different ways to redeploy your money in the stock market. You can buy back in either all at once or by dollar-cost averaging (contributing a set amount at certain intervals).

Keep in mind that having too much in cash comes with inflationary risk. If you put all your money in a savings or money market account, it would need to earn more in interest than the current rate of inflation for you to not lose purchasing power over time.

While being in the market means lots of volatility, waiting in the wings can also mean missing out on the gains in between the drops.

“If you sat tight in 2008 and 2009, you got to enjoy the recovery,” Levine said. “It’s the people who panicked at the bottom and sold who suffered.”

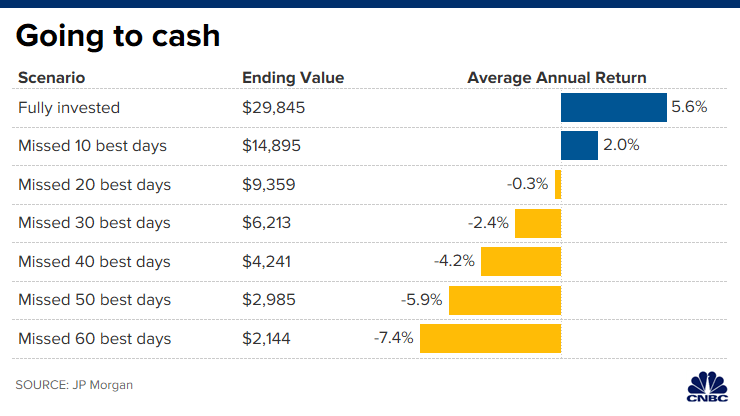

The chart below shows how $10,000 invested in the S&P 500 index, for the 20-year period of 1999 through 2018, would have performed under various scenarios.

If the $10,000 remained fully invested, it would have grown to $29,845 with an average annual return of 5.6%.

In comparison, missing out on just the best 10 days in that time period would have reduced the growth of the initial investment by more than half: After 20 years, that $10,000 would be just $14,895 with a 2% average yearly return.

If the best 20 or more days were missed, the returns over that 20-year period are in the red. And six of the S&P’s 10 best-performing days during the 20-year period occurred within two weeks of the 10 worst days, according to J.P. Morgan.

For example, the worst single day in 2015 — Aug. 24, when the S&P dropped nearly 4% into correction territory — was followed two days later by the year’s best day of returns (again, nearly 4%).

Additionally, if you own stocks that pay dividends, you’ll also miss out on those periodic payments.

Of course, there’s always the chance that you could get the timing right — i.e., you sell at the top of the market and buy at its bottom.

For illustration purposes only: Say you had sold 10 shares of an S&P 500 fund when the index peaked in October 2007 at 1,565, and then repurchased shares when it bottomed in March 2009 at 666. In that case, your money would buy 23 shares — more than double the amount you sold.

At the same time, though, you would have missed five dividend payments and, once reinvested, their future gains, as well.

More important, recognizing both the top and bottom is tricky.

“While some people get lucky with timing the market, it’s the worst thing you can try to do,” Levine said.

The post Here’s how to get back in the stock market if you sold out of fear when it was down appeared first on CNBC news and is written by Sarah O’Brien

Original source: CNBC news