Assertions are claims made by business owners and managers that the information included in company financial statements — such as a balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows — is accurate. These assertions are then tested by auditors and CPAs to verify their accuracy.

Overview: What are audit assertions?

Whether you’re with a Fortune 500 company, a nonprofit, or are a small business owner, any time you prepare financial statements, you are asserting their accuracy. Audit assertions, also known as financial statement assertions or management assertions, serve as management’s claims that the financial statements presented are accurate.

When performing an audit, it is the auditor’s job to obtain the necessary evidence to verify the assertions made in the financial statements. Whether you’re using accounting software or recording transactions in multiple ledgers, the audit assertion process remains the same.

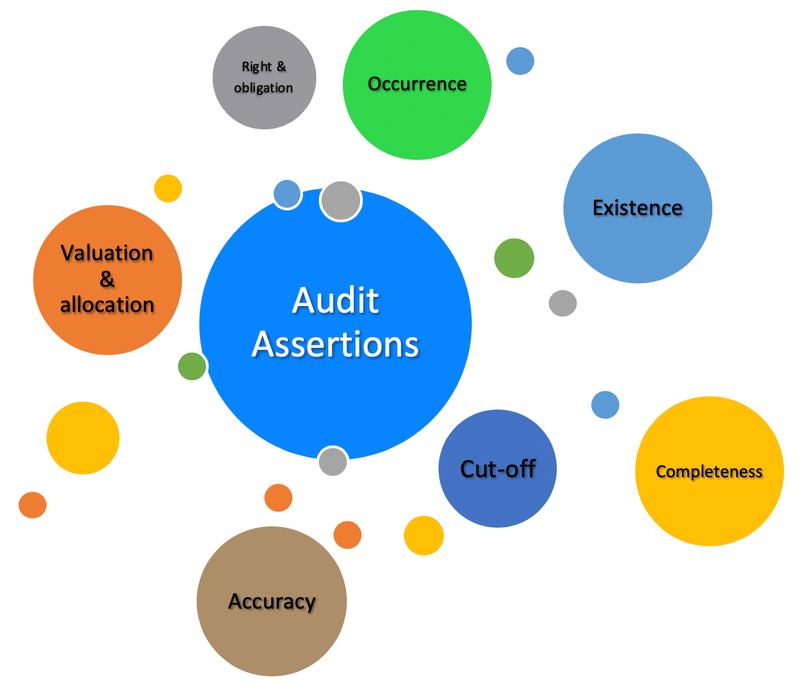

Types of assertions

There are numerous audit assertion categories that auditors use to support and verify the information found in a company’s financial statements.

1. Existence

The existence assertion verifies that assets, liabilities, and equity balances exist as stated in the financial statement. For example, if a balance sheet indicates inventory on hand for $10,000, it is the job of the auditor to verify its existence.

The same process is used when verifying accounts receivable balances. The auditor is tasked with authenticating the accounts receivable balance as reported through a variety of means, including choosing a particular accounts receivable customer and examining all related activity for that particular customer.

Bank deposits may also be examined for existence by looking at corresponding bank statements and bank reconciliations. Auditors may also directly contact the bank to request current bank balances.

2. Occurrence

The occurrence assertion is used to determine whether the transactions recorded on financial statements have taken place. This can range from verifying that a bank deposit has been completed to authenticating accounts receivable balances by determining whether a sale took place on the day specified.

3. Accuracy

Accuracy looks at specific transactions and then checks the accuracy of the recorded entry to determine whether the amounts are recorded correctly. In many cases, an auditor will look at individual customer accounts, including payments. to verify that the amount recorded as paid is the same as received from the customer.

4. Completeness

Completeness helps auditors verify that all transactions for the period being examined have been properly entered in the correct period.

For example, an auditor may want to examine payroll records to make sure that all salaries and wages expenses have been recorded in the proper period. This may include an examination of payroll records, a payroll journal, an active employee list, and any payroll accruals that were made and reversed in the period being examined.

Inventory can also play a large role in the completeness assertion, with auditors looking at inventory transactions that took place during a specific period by examining inventory levels and corresponding sales numbers to determine that inventory was recorded properly.

Completeness, like existence, may examine bank statements and other banking records to determine that all deposits that have been made for the current period have been recorded by management on a timely basis. Auditors may also look for any deposits in the bank that have not been recorded.

5. Valuation

The valuation assertion is used to determine that the financial statements presented have all been recorded at the proper valuation.

For instance, the reporting of a company’s accounts receivable account does not provide a guarantee that the customer will pay the accounts receivable amount owed. In this case, an auditor can examine the accounts receivable aging report to determine if bad debt allowances are accurate.

Inventory is another area that auditors may review to determine that inventory is properly valued and recorded using the appropriate valuation methods.

6. Rights and obligations

Rights and obligations assertions are used to determine that the assets, liabilities, and equity represented in the financial statements are the property of the business being audited. In other words, if your small business is being audited, the auditor may ask for proof that the cash balance of your bank account belongs to the business.

Auditors may look at other assets as well to determine whether they are the property of the business or are just being used by the business. Liabilities are another area that auditors will review to determine that any bills paid from the business belong to the business and not the owner.

7. Classification

The classification assertion addresses the financial statements themselves. Are the statements presented properly in an acceptable format? Do they include all of the necessary information and related disclosures? Are they easy to understand?

For example, accounts payable notes payable and interest payable are all considered payables, but they are all very separate entities and should be reported as such. For example, notes payable transactions should never be classified as an accounts payable transaction, with the same being true for interest payable transactions.

It is the auditor’s responsibility to determine that these items are properly disclosed in the financial statements.

8. Cut-off

The cut-off assertion is used to determine whether the transactions recorded have been recorded in the appropriate accounting period. Payroll and inventory balances are often checked for cut-off accuracy to determine that the activity that took place was recorded in the appropriate period. This is particularly important for those accruing payroll or reporting inventory levels.

The audit assertions above are used in three different categories.

| (Used when examining journal entries and transactions) | (Used when examining asset, liability, and equity totals) | (Used to determine proper format and clarity) |

Completeness, Accuracy, Classification, Occurrence, Cut-Off | Rights & Obligations, Existence, Completeness, Valuation | Accuracy, Occurrence, Completeness, Classification |

Audit assertions frequently asked questions

What is an audit?

An audit is the examination and evaluation of the financial statements of a company performed by an objective third party. The purpose of an audit is to make sure that the information contained in financial statements is fair and accurate and that a business is in compliance with all necessary rules. Publicly held companies are required to have an audit of their financial statements annually.

Are financial statement assertions the same as audit assertions?

Yes. Audit assertions are also known as financial statement assertions or management assertions. Whatever term you use, the meaning is the same.

Why is it important for small business owners to understand audit assertions?

The word “audit” can make anyone’s blood run cold. If you’re entering your financial transactions properly, you don’t have anything to be worried about. However, understanding what auditors are looking for can help to ease your panic.

Auditors examine transactions made such as journal entries, financial statement balances, and the overall appearance, readability, and formatting of financial statements during an audit. Knowing this beforehand will help you be better prepared for the process.

Audits don’t have to be scary

Your financial statements are your promise or your assertion that everything contained in those statements is accurate. The job of an auditor is to test those assertions for accuracy. Unless you’re an auditor or CPA, you’ll never have to worry about testing audit assertions, and if you continue to enter financial transactions accurately, you won’t have much to worry about during the audit process.

However, knowing what these assertions are and what an auditor will be looking for during the audit process can go a long way toward being better prepared for one.

The post Understanding Audit Assertions and Why They’re Important appeared first on The blueprint and is written by Mary Girsch-Bock

Original source: The blueprint