I’ve spent a lot of time watching Antiques Roadshow on PBS, where appraisers sometimes shock everyday people by sharing sky-high valuations for dusty family heirlooms that appear worthless. It’s incredibly heartwarming to watch people stumble upon a small fortune for things they’ve proudly displayed in their homes for generations.

Fair value accounting might not give you the same warm and fuzzy feeling, but it’s an essential part of understanding your business’s value.

Overview: What is fair value accounting?

Fair value accounting involves measuring your business’s assets and liabilities — anything it owns and owes — at their market value. Instead of valuing your business based on purchase prices, you periodically update values to reflect what they’re worth today.

You’re probably more familiar with the historical cost method of accounting, where you record an asset’s purchase price on your financial statements until they’re sold or trashed. Fair value accounting more precisely values your company, but it requires more effort to maintain.

For example, let’s say a company purchased land for $500,000 five years ago, and a land appraiser says it’s worth $600,000 now. A historical cost balance sheet will value the land at $500,000 until it’s sold. The fair value method of accounting would adjust the land’s value to $600,000.

For financial reporting purposes, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) require the historical cost method for most types of assets, including land. That’s good for small businesses because the historical cost approach is simple: Record the asset purchase transaction on day one and don’t change it until the asset is sold or disposed of.

While it’s uncommon for small businesses, there are two instances in which you might have to report an asset’s fair value on your financial statements: impaired assets and certain investments.

If an asset loses significant value — either by damage or from market conditions — you’re required to impair, or reduce the asset’s value, on your books. Say your business’s land is swallowed by a sinkhole, making it lose 40% of what it’s worth. You’ll have to adjust its value in your books.

You also use the fair value method for investments that don’t relate to the business’s operations. For example, an ice cream shop that owns its land would record the asset on its books at the historical cost. If the ice cream shop used earnings to invest in the stock market, the investments would be listed at fair value.

While you probably won’t use the fair value approach for financial reporting, you still might want to build a fair value balance sheet where all assets are listed at their market value. Potential investors and lenders will consider the market value of assets to piece together a business valuation.

4 fair value accounting concepts

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and GAAP share a definition of fair value, calling it “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.” Let’s break that down.

1. Orderly transaction

An orderly transaction is where the seller is not in a rush to sell, giving your asset the time to find the right buyer willing to pay a fair price.

Think of it like selling your home. You might put a lower-than-market asking price on the house when you need to move quickly. With more time, you can wait for someone to buy it at a fair price.

2. Market participants

A fair value transaction occurs between two unrelated parties with a strong understanding of the market in which they’re operating. It’s not like you selling a car at a discount to your friend because of that one time he helped you move apartments.

3. Measurement date

The fair value of an asset or liability considers market conditions on the valuation day. Your car might be worth $5,000 on a Monday, but after a tree falls on it on Tuesday, it could be totaled. Investors and lenders often bring in their own appraisers for big-ticket items to make sure your fair valuation is accurate and hasn’t changed since the measurement date.

4. Principal or most advantageous market

The final concept assumes that you’re in an environment that maximizes an asset’s selling price or minimizes a liability’s transfer price.

For example, say you’re selling your old cell phone because you just bought a new one. You can sell it online for $250, but a kiosk at the mall will give you $150 for it. The phone’s fair market value is $250.

How to determine fair value

The fair value of an asset or a liability reflects what you can sell or transfer it for in the market, but it’s hard to know the exact amount unless you do it. Let’s try to find the fair value of a silver 64 GB iPhone X today (October 2020).

1. Find comparables

Look to the marketplace where similar assets are sold and liabilities are transferred. Pay attention to assets and liabilities that were recently sold or transferred, not ones that haven’t yet sold or been transferred. You can put a used iPhone on the market for any price; you only care about the selling price.

According to IFRS and GAAP, the best information you can find is what they call “level one” inputs: sales prices for identical assets and liabilities. In our iPhone example, a level one input would be a list of secondhand, same color, same size iPhone X sales made today.

When level one information isn’t available, move onto “level two,” which would be similar but not identical assets and liabilities. An iPhone X in a different color would fall under the level two category.

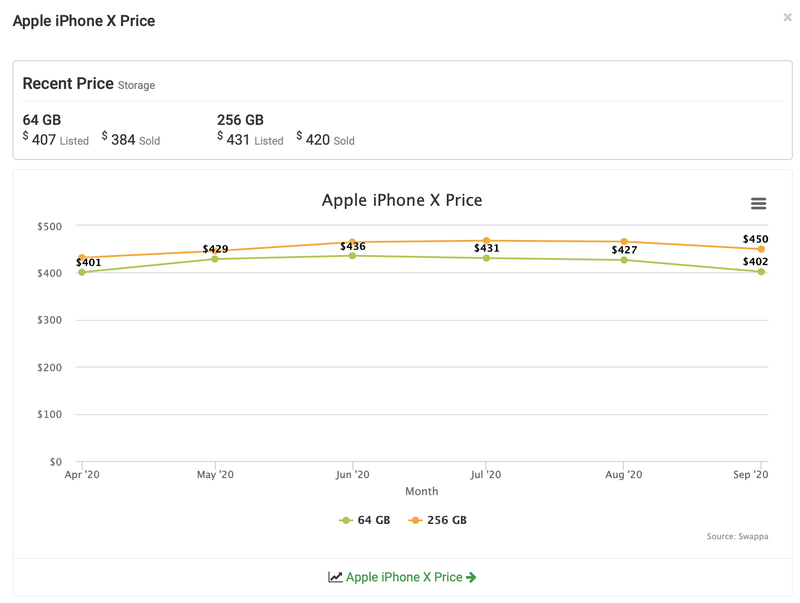

To calculate the fair market value for an iPhone, you can use websites like Swappa that share detailed pricing information (for a fee). They share limited data for free, like the recent average selling price of most popular models. Swappa says an iPhone X with 64 GB in storage has been selling for an average of $384 over the past few months.

2. Consider bringing in a professional

When nothing like your asset or liability is on the market, you have to fall back on what the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and GAAP call “level three” information. Level three information comes from internal data from your accounting software and professionals who can use their judgment to estimate the value.

Professionals can create models that estimate the income your asset will generate in the future — called its future cash flow — to determine fair value. You might be asked to produce metrics like the asset turnover ratio to create a precise fair value.

Even if there are comparables on the market, you might call on an appraiser to determine your asset or liability’s fair value. They might have access to more information than you do and can deliver a more precise estimate.

Fair is fair

You’ll never know an item’s value until you sell it, so fair value accounting is all about getting the best estimate possible given the information you have. If you’re not feeling confident in your fair valuation calculation, talk to an expert.

The post A Small Business Guide to Fair Value Accounting appeared first on The blueprint and is written by Ryan Lasker

Original source: The blueprint