Do retirees have an alternative if they believe that bonds are guaranteed to lose to inflation and stocks’ outlook is too uncertain?

It’s an urgent question. Given plunging interest rates, the 10-year Treasury currently yields minus 0.50% after inflation (assuming the current 10-year break-even inflation rate of 1.18%). And even Warren Buffett, who has made a career being a cheerleader for stocks’ long-term potential, said at Berkshire Hathaway (BRK)(BRK) annual meeting several weeks ago that he’s not buying stocks right now because he does not “see anything attractive.”

Many retirees and soon-to-be retirees are looking to gold as an alternative.

Many believe it’s attractive because of the presumably inflationary consequences of the Fed’s aggressive money printing to stimulate the economy. Gold’s price has been bid up to its highest level in eight years and within shouting distance of its all-time high.

But this inflation-based argument on behalf of gold is hard to square with a model that the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank has devised to derive from various markets what investors collectively expect inflation to be in coming years. Currently, that model says that expected inflation is just 1.16% annualized over the coming decade. That’s the lowest this rate has been in at least four decades, which is how far the bank’s model extends.

It could be that gold is right and the other markets are wrong, of course. But I wouldn’t be too sure of that. The Cleveland Fed’s model is based on “Treasury yields, inflation data, inflation swaps, and survey-based measures of inflation expectations”—markets that collectively have far more money at stake than the gold market.

To be sure, it could very well be that the Fed’s money printing will be inflationary down the road. But Claude Erb, a former commodities portfolio manager at TCW Group, reminded me in an email that “during the Global Financial Crisis there were some gold types who thought that Quantitative Easing was money printing and that QE-inspired money printing would lead to significant inflation.” And, yet, it didn’t turn out that way: The CPI over the last 10 years has grown at a lower than it did over the prior 10-year period.

In fact, many economists today are more worried about the prospect for deflation than inflation.

Do low interest rates justify a high gold price?

Perhaps in frustration at the lack of the high inflation that they’re looking to in order to justify a higher gold price, some gold bulls have turned to another argument: Today’s record-low interest rates. One rationale for this argument is that lower rates reduce the value of the U.S. dollar, which in turn leads to a higher dollar-denominated gold price. Another is that low rates make bonds and other fixed-income investments less competitive, which should help gold in relative terms.

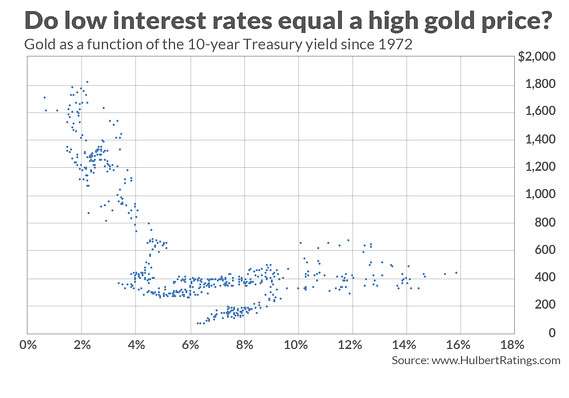

There certainly is strong historical support for this argument, as you can see from the accompanying chart: There is a significant negative correlation between gold and the 10-year Treasury yield.

How significant? Consider the correlation coefficient, which measures the degree to which one data series (in this case, gold) is correlated with another (in this case the 10-year Treasury yield). This coefficient ranges from a maximum possible +1.0 (which would mean that the two move in lockstep with each other) and a minimum possible minus 1.0 (which would mean that the two move in precisely the opposite directions from each other). Since 1972, the correlation coefficient between gold and the 10-year yield has been minus 0.66, which is statistically significant.

There’s a crucial flaw to using this argument to justify being bullish on gold, however: It directly contradicts the argument based on gold being a good inflation hedge. It’s unlikely that both arguments can simultaneously support a higher gold price.

Imagine, for purposes of argument, that the Treasury’s 10-year yield rises back to its early-1980s level of nearly 16%, which is entirely plausible should inflation return to its double-digit level that then prevailed. According to Erb, the historical correlation between the two would suggest that gold’s price would fall to around $400 an ounce.

That’s hardly consistent with gold rising as a hedge against inflation.

The only way that both the inflation-hedge and interest-rate-correlation arguments can simultaneously support a higher gold price is to forecast what might be called an inflationary depression. Try as I might, however, I can’t imagine an economy in which inflation skyrockets and interest rates remain at rock bottom levels.

The closest analog in U.S. history to an inflationary depression is to the stagflation of the 1970s, in which interest rates—far from plunging—more than doubled.

The bottom line?

Perhaps the most crucial investment lesson to draw from this discussion is not to cherry-pick the data to justify your predetermined conclusion. That’s important to keep in mind at any time, but especially now, when our urgent search for an alternative to stocks and bonds can lead us to place greater faith in gold than the historical data justify.

This isn’t to say that a smallish allocation to gold isn’t a good portfolio diversifier. Just be careful when contemplating larger bets that could expose your portfolio to undue risk.

The post Opinion: Does gold belong in a retirement portfolio? appeared first on MarketWatch and is written by Mark Hulbert

Original source: MarketWatch